- Главная

- Daria Dugina: The Traditionalism, The Philosophy and The Russian World

Daria Dugina: The Traditionalism, The Philosophy and The Russian World

Art by Alexey Belyaev-Gintovt, contemporary Russian artist.

https://vk.com/alexeygintovt , https://www.facebook.com/guintovt

Compilation of texts and thoughts by Daria Dugina narrated in English, about The Traditionalism, The Philosophy and The Russian World and quotes from her book and poems, so that her soul will be remembered for all eternity.

Listen to audio

Watch the video

-

La Cantata scenica di Darya Dugina a Belgrado

-

Eurosiberia Podcast #47: Daria Dugina’s Radical Life

Jafe Arnold from PRAV Publishing and Constantin von Hoffmeister discuss Daria Platonova Dugina’s life, death, philosophy, and legacy.

Order Eschatological Optimism here.

Order For a Radical Life here.

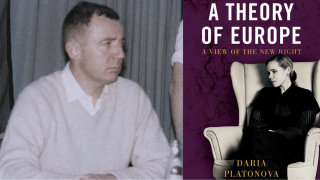

Order A Theory of Europe here.

-

World Premiere of the Scenic Cantata for Daria Dugina

World Premiere of the Scenic Cantata entitled Daria Dugina, created by Italian composer A. Inglese and performed by Italian musicians and singers E. Tsarenko, F. Armiliato, A. Rossano, G. Musillo, L. Di Ionna and M. Inglese.

-

The Poor Subject - Daria Dugina

Russian as an Enigma1

Russian thought lives where night parts with the day, in the cold dusk of the Russian forest. There is no “Russian philosophy” as such, and such a thing could never come to be. Philosophy means touching upon secrets, upon what is concealed, and vertically ascending to the heavenly world beyond.

Where are we to go if the beyond is within us? Russians have no border between “there” and “here.” We live in “herebeing.” And in here-being, we experience the sacred in every moment of our lives. Our thought is woven with dreaming and enmeshed in the structure of dreams.

Russians are spirit-seers. Our thought cannot grasp what it comprehends. It is what it comprehends. In our land, in the space of our soul, the comprehended and the comprehending merge. This is the mysterious, secret course of things, the frantic course of things. We have no subject — it is absolutely poor. We have no object — it is negligible and small. Perhaps, Russians today are in their thought and existence closest of all to authenticity. We do not comprehend this — we live it. It pierces the structure of the Russian soul, it cuts into our inner tissue, at times painfully.

Witnesses of the God-Forsaken

In the West, the subject stands at the center of everything, or rather, it once stood there before they destroyed it. First, the West was forsaken by God, and now it has been forsaken by the subject.

But us? We have something else. We are hurt by the Godforsakenness of Europe, we are the witnesses of Europe’s having been forsaken by God. We are God-bearers. We are the witnesses of subject-forsakenness, but… the Russian subject — what is it? A poor subject. So big that it starts to seem too small and poor. This poverty is not poverty in the sense of lack or need, but rather a poverty that surpasses riches and emeralds. It is like the poverty of a monk. The subject is so poor that it is almost absent– its will, its intention, is barely visible through the fog of the indistinguishable. Not only does it lack a trajectory, it lacks any point of initiation for a trajectory — no intending, no intended, no intention.

The Russian subject is the poor subject, a secret, mysterious force, the sphere of subtle being. This is real existence. It is hope that is not directed towards anything. It is Being itself. The Russian is too broad to be a subject. This meek, humble, directionless poverty is something confused, and hardly understands its own true wealth — that which, without being known, is already at the center of Being, at the center of Absolute Truth, at the center of the eternal light of the Good, in the punishment of the soul, where words are too exhausted to express the infinity and greatness of God.

References:

1. The present text was a speech delivered at the premiere of the late Andrei Iryshkov’s multimedia project and documentary film The Feminine Principle in Russian Philosophy at the Gorky Art Theater in Moscow on 27 January 2020.

Excerpt: from Eschatological Optimism by Daria Platonova Dugina

Translated by Jafe Arnold

https://pravpublishing.com/eschatological-optimism/

https://t.me/PRAVPublishing

-

Post-politics vs. existential politics - Daria Dugina

The 20th century was a century of rivalry between three ideologies. Some managed to reign for several centuries (liberalism), others for decades and years (communism and national socialism). But their demise seems obvious to us. All three ideologies, daughters of the New Age philosophy, have left the space of politics. The era of modernity has come to an end.

The end of the modern era

The death of liberalism does not seem as obvious as that of communism or national socialism. Francis Fukuyama proclaims 'the end of history', i.e. the end of the rivalry between the three ideologies and the final victory of the liberal doctrine. But liberalism did not win... This can be seen by paying attention to the subject of politics today. If in classical liberalism the subject of politics was the individual (its main virtue was freedom in the negative sense: accurately described by Helvetius, 'A free man is a man who is not chained, is not imprisoned, is not intimidated like a slave by the fear of punishment...'), today this individual no longer exists. The subject of classical liberalism is eliminated from all spheres, his wholeness is distrusted, his identity, even if negatively posed, is characterised as a failure in the functioning of the global virtual system of modernity. The world has entered the realm of post-politics and post-liberalism.

Rhizomatic politics

The individual has turned into a rhizome, the contour of the subject has dissolved with the belief in the New Age ("There has been no New Age!" proclaims Bruno Latour, noting in modernity the many contradictions and the failure to respect its own rules of operation - the constitution). "We are tired of wood", the logos of modernity is mocked by the liquid and fused society of postmodernity. A new actor in politics emerges: the post-subject. He thinks chaotically: slides change in his head at the speed of light, interfering with classical logical thinking strategies. The new thinking is that of a chaotic stub, glitch thinking. Politics is transformed into a wonderland in which the actor-evidence-Alice now increases, now decreases in the psychedelic scheme of the new post-rationality.

The contemporary left and right are an example of this pattern. The recent coalition of left and right against the National Front after the first round of the regional elections showed the end of the political model of modernity. The fusion of the values of the left and the right, united by a new kind of liberal virus. The modern left starts flirting with capital, actively defends the political values of the right (ecology) and the right takes on the comical character of fake nationalists.

A characteristic of post-politics is the blurring of the contours of the scale of the 'event'. The scale shifts dramatically ('Alice grows, Alice shrinks'). The modern confrontation between the system and terrorism has been called the Fourth World War by Baudrillard. In contrast to previous wars - the 1-2 world scale, WW3 - the confrontation of the two key geopolitical poles (US and USSR) - a softpower, semi-medieval war with the readiness to become a war with new weapons at any time; WW4 - a post-modernist war in which both enemy and friend are deftly intertwined (terrorism becomes part of the political system). WW4 flirts with scale: its main characteristic is randomness, chaos and arbitrariness in defining the scale of the event (the micro-narrative becomes the event, macro-narratives are ignored). A terrorist act occupies a small area: a building, a corridor, a few rooms or terraces (micro-narrative). But its significance is as great as the battle of Stalingrad (macro-narrative).

In classical wars, there were reference points against which we could relate the event and its meaning. In the modern political world, there are no reference points: it is like Alice in Wonderland. Now it decreases and then increases, but its 'normal, ideal' growth is impossible to identify (the chaos described by Deleuze in The Logic of Meaning). The logic of the political is abolished.

The terrorist attacks (130 dead - Paris, Friday 13) shake 'politics' more than large-scale wars (Syria). This shows that the world is entering a new phase: that of rhizomatic politics. To understand contemporary politics, we must learn to think in rhizomatic terms. Absorb the chaos.

Post-politics is a world of political technology, 5 seconds left-wing, socialist - 5 seconds right-wing, republican. Identity changes with the click of a TV remote control, technology. (Only the question arises: who controls the remote control, who decides to change the slide?) In Martin Heidegger's terms, the main force of modern post-politics: the machenschaft und tehnne.

An alternative to rhizomatic politics in a situation where ideologies are dead

Heidegger's writings offer a particular perspective on the organisation of the political. In liberal Western society, Heidegger's work and especially his political philosophy (which is not given explicitly) have not been sufficiently explored. As a rule, the study of Heidegger's political philosophy is reduced to an attempt to find in the philosopher an apologia for fascism and anti-Semitism (an example of this is the reaction of the philosophical community to the recent publication of the Black Notebooks, particularly eloquent from the French historian of philosophy Emmanuel Faye). Such an interpretation ignores the metaphysical dimension of Heidegger's philosophy and seems unnecessarily superficial and distorting of Heidegger's teaching.

Martin Heidegger cannot be interpreted in the context of any 20th century political theory. His critique of machenshaft applies not only to the Jews (and not on a biological, but on a metaphysical principle), but also, to a much greater extent, to National Socialism. In this sense, we can say that Heidegger represents a fundamental critique of National Socialism, in which he sees manifestations of machenshaft (as opposed to the 'spiritual', authentic National Socialism - which, according to Heidegger, was not realised under Hitler's rule).

Heidegger recognises a profound crisis in political systems. Applying the history of being to the history of the political, politics appears as a process of gradually forgetting being and approaching being. The modern political has no existential dimension, it exists in an inauthentic way. Politics and ontology are inseparable, Plato had already emphasised this in the Republic when he introduced the homology between the political and the ontological ('justice in the soul is the same as justice in the state').

Applying fundamentalistontology to the realm of the political, we can suggest that the political can exist authentically and inauthentically. The authentic existence of the politician is his commitment to being, the inauthentic one is his excessive preoccupation with being, his oblivion of being. The state in which the politician becomes authentically existential is hierarchical. The ontological stands above the ontic. The authentic over the inauthentic. The types of domination lie in a strict vertical line: from mahenschaft to herschaft.

In today's situation of crisis of the 'political', existential politics deserves special attention and seems to us a true alternative to rhizomatic politics. It needs in-depth study and further development.

Translation by Lorenzo Maria Pacini

-

The novel Laurus as a manifesto of Russian traditionalism - Daria Dugina

The novel-life, a 'non-historical novel' as the author Evgeny Vodolazkin (doctor of philology, specialist in ancient Russian literature) calls it, is a description of the destiny and inner development of Arseny the healer. After receiving medical training from his grandfather Christopher, Arseny enters life with all its complexities, temptations and trials. From the beginning, Arseny's profile betrays a man called in spirit and marked by a special gift, an unusual charisma. He is mobilised by a higher power to serve people. He is not of this world, but he serves people of this world. Already in this we can see the plot of suffering and pain.

During a plague, Ustina, a poor girl whose village has been hit by an epidemic, arrives at Arseny's house. The young healer welcomes her as he welcomes all those in need of help and succour, those who are in distress and have nowhere else to go and no one to turn to. Arseni lets her into his home, takes her in, gives her shelter and... they grow up together. Too much. And above all - without the sacrament of the church obligatory for a man from Old Russia. This means their union is sinful and brings with it pain, suffering, death and a dark end. Ustina becomes pregnant, but for fear of censure and reproach, Arseni does not take her to the wedding. Moreover, it is not clear how to explain that she was saved from the plague. So love turns out to be a sin, the child is the result of a fall, and on top of this complicated situation before the birth, which Arseniy himself is forced to take, Ustina does not receive communion, because how to explain her situation to the confessor?

And so the worst thing happens. Ustina dies during excruciating labour, the baby is stillborn. Arseny almost loses his mind with grief and the knowledge of his complicity in the horror that has occurred. Ustina and her stillborn child, who was not baptised, do not even deserve a proper funeral by the standards of the time; the woman in labour was not married and the child died unbaptised. Both are buried in the Bogedomk, a special place outside the Christian cemeteries where the corpses of vagabonds, ophi, sorcerers and clowns are thrown. Together with Ustina, the previous Arseni dies and a new one is born, Ustin, who takes as his name the male version of the name of his beloved, his victim and his sin. Thus the hero begins his path: the path of repentance, heroic deeds and suffering to overcome the enduring spiritual and metaphysical pain of his youth, detached from the axis.

Arseny-Ustin later becomes a famous herbalist and healer, his fame spreading throughout Russia. But this is only a stage. Then comes the time for a new 'transition'. And he moves along the chain of ancient Russian spiritual figures: madman, old man, prophet. The madman Thomas gives the hero a new name - from now on it is Amvrosy, and in turn he undertakes the feat of madness, achieving holiness and impassibility in voluntary humiliation and atypical - sometimes provocative - behaviour.

This is followed by a pilgrimage to Jerusalem with the Italian monk Ambrose and, on his return from the arduous journey, the assumption of the rank of monk and so on, all the way to the highest monastic order, the schema. Thus from Arseny Ustin was born Laurus - from the pain of the soul, seeing the body of his beloved Ustina thrown into the goddess; from witnessing the death of the monk Ambrose; from observing the elements during storms, in which sailors perished; from the general injustice of the world and the quagmire that covered Russian (and non-Russian) lands; from the infinite Russian spaces and souls, beyond the comprehension of both foreigners and Russians themselves.

"What kind of people you are," says the merchant Siegfried. - A man cares for you, he devotes his whole life to you, you torment him all his life. And when he dies, you tie a rope to his feet and drag him, and you are in tears.

- You have been in our land for a year and eight months already,' says the blacksmith Averky, 'and you have understood nothing of it.

- And you yourselves understand it? - Siegfried asks.

- Do we? - The blacksmith hesitates and looks at Siegfried. - Nor, of course, do we understand it ourselves.Milestones of human life Traditions

Arseny - Ustin - Amvrosii - LaurusLaurus' life, which in his hagiography is divided into several cycles - childhood/youth/maturity/old age and 'sannyasa' (the life of a hermit who completely renounces the world) - the life of a man of the Tradition.

In the description of Laurus' ascetic life, the Indo-European canon of the life of a man of Tradition (vividly described in the Manu-smriti and other Hindu scriptures) striving for liberation, consisting of four cycles, is manifested. The novel, like the life of Laurus, is divided into four parts: 'The Book of Knowledge', 'The Book of Renunciation', 'The Book of the Way' and 'The Book of Rest'. According to the Upanishads, liberation becomes possible if one lives the three ashrams (three stages of life) with dignity:

1) Study of the Vedas, discipleship (brahmacharya) - the first stage of Arseni's life - learning from the wisdom of his grandfather Christopher

2) Home and sacrifice for wife and family (grihastha) - Arseniyya's family, Ustina's death and further acceptance of her in herself - constant dialogue with the deceased lover

3) The years of hermitage in the forest (vanaprastha) - both herculeanism and wandering and the journey to Jerusalem

4) The last ashram period (sannyasa) - associated in Hinduism with withdrawal from worldly affairs and full devotion to spiritual development, it is a period of meditation and preparation for death. In Hindu tradition, it was very important to die homeless, naked, alone, an unknown beggar. This is how Laurus dies, after being slandered.It is important to note that at each of these stages of life in the Tradition there was a change of name. Thus, we readers witness a sequence of 4 characters - Arseny, Ustin, Ambrosius and Laurus - each manifesting 4 different stages of human formation in Indo-European tradition.

"I have been Arseny, Ustin, Ambrosius, and now I am Laurus. My life is lived by four different people who have different bodies and different names. Life is like a mosaic and it falls apart,' says Laurus.

Being a mosaic does not mean falling apart, Innocent replied. You have broken the unity of your life, you have given up your name and identity. But even in the mosaic of your life there is something that unites all its separate parts, it is the aspiration to Him (God - author's note). In Him they will be reassembled,' replies Elder Innocent.

Four different lives, stages, images, faces-personalities merge into one face. The passage of the four stages of life in the novel is the successive ascent of man from the lowest to the highest, from material manifestation to the highest realisation - the theurgic sacrament. What is described in Laurel is the Neo-Platonic experience of the soul's return to its source, the Good, the One. The novel can be considered in the Neoplatonic scheme of the ascent of creation to its ineffable source.

These four periods in the protagonist's life also have a social, caste dimension: the ascent from one stage to the next is also a change of social status. From disciple to 'husband', from 'husband' to hermit, from hermit to monk and hermit. All this is a movement along the vertical axis of social strata: while in the first part Arseny has a house, books, herbs and a small territory, at the end of the book he has no walls and his refuge is the stone vaults, the trees and the forest. Thus, moving on to a new phase, Arseny also separated himself from Christopher's books. The new hero, the philosopher and guardian, is not fit to have any private property. He cannot have anything, because the possession of something means weakening the tension of contemplation of the high. At the end of the novel, Laurus has nothing, all his food is that of birds and beasts, he no longer even belongs to himself. He belongs to the Absolute.

The problem of time and eternity in the novel Laurus

One of the novel's main themes is the problem of the interpretation of time: material time in Laurus, following Platonic topics, is understood as "the moving simulacrum of eternity". Two dimensions seem to coexist in the novel: a linear time leading to the end (the eschatological line of the novel comes from the West - Ambrose comes to Russia to find the answer to the question of the date of the end of the world), a Judeo-Christian dimension and an eternal-mythological dimension, originating in the ancient tradition, which in Christianity has become a dimension of the circular cycle of worship, which simultaneously appears as a spiral and turns into a paradox: Reproducible events - the festivals of the Church - which occur 'again' each time, come true as if they had never happened before. Each time, events similar in meaning appear different (a conversation between Laurus and Elder Innocent: 'Because I love geometry, I liken the movement of time to a spiral. It is a repetition, but at a new and higher level'). Even the narrative itself, the life of Arseni Arseny us reproduces the spiral - many events in the novel are similar, but each time they occur at a new 'higher level' (e.g. at the end of his life - Arseny, formerly Laurus, gives birth again, this time the mother in labour does not die, and the baby survives).

'There are similar events,' the elder continued, 'but from this similarity comes the opposite. The Old Testament is inaugurated by Adam, but the New Testament is inaugurated by Christ. The sweetness of the apple eaten by Adam is revealed to be the bitterness of the vinegar drunk by Christ. The tree of knowledge leads man to death, but the tree of the cross gives man immortality. Remember, Amvrosius, that repetition is given to us to overcome time and our salvation.

The coexistence of the two dimensions - temporal and eternal - is also evident in the very structure of the narrative: in Lavra, the descriptions of medieval Russian life are intricately interwoven with contemporary episodes, the protagonist lives with the dead - he constantly talks to them, discusses them, talks about his experiences. This structure is largely related to postmodern novels. Vodolazkin is certainly a postmodernist in his technique. However, by filling the 'collage' with plots from different milestones, he places the deep traditionalist meanings above the technique. In the novel, the coexistence of several epochs is shown in a particularly subtle and vivid way: we find ourselves in medieval Russia, then we move into the modern world with researchers, book lovers and historians, then we find ourselves witnessing Soviet terminology - Vodolazkin has succeeded in a very clever and organic way in showing synchronism, the parallel existence of several epochs and dimensions. Just as different slices of time coexist in the novel, so in us today there is both the archaic and the future. We today are our ancestors, watching the rapidly changing world through our eyes, and our future children.

The novel 'Laurus' is a large-scale manifesto of Russian traditionalism, an embodiment of the Russian paradox of the coexistence of time and eternity in us, of this Indo-European canon of hagiography dressed up as medieval znakhar, of this myth of eternal return and cutting through this myth with the arrow of time, heading towards the end of the world. 'Laurel' is a manifesto of the vertical movement. The one we have forgotten behind the frenzy of everyday life. And it manifests itself so clearly in times of pestilence. Then and now.

"Isn't Christ the general direction?" the elder asked. What direction are you still looking for? And do not be carried away by the horizontal movement beyond measure. And of what?" asked Arsenius. Vertical movement, replied the elder and pointed upwards.

Translation by Lorenzo Maria Pacini

-

The apophatic tradition: the theology of Dionysius the Areopagite - Daria Dugina

The work of the famous Christian theologian and mystic, whose writings have entered the Christian tradition under the name of Dionysius the Areopagite, is a unique phenomenon in the history of philosophical and religious thought. He has had an enormous influence on all Christian philosophy, eastern and western, and consequently on New Age philosophical thought in one way or another since the Middle Ages, where the Areopagitans played such an important role.

Almost all scholars of the Areopagitic Corpus agree that it is Platonism in Christian form. Consequently, we must place it in the general context of Platonic philosophy in order to understand its place and dissect its characteristics.

The Areopagitics are reliably known from the 5th century AD. Thus they are separated from Plato himself and his Academy by about 10 centuries. During this time Platonism underwent a series of fundamental metamorphoses, institutionalisations and interpretative shifts, which must be traced in the most general way to understand the historical-philosophical process from Plato (5th - 6th century BC) to the Areopagitics (5th century BC).

This period can be divided into three phases:

1 - Post-Platonist Academy (Speusippus, Xenocrates, etc.), of which few reliable testimonies are known and whose philosophical specificity is problematic today due to the extremely scarce testimonies;

2 - Middle Platonism (Posidonius, Plutarch of Cheronia, Apuleius, Philo);

3 - Neoplatonism, which arose in Alexandria and from the beginning was divided into two schools: pagan (Plotinus, Porphyry, etc.) and Christian (Clement of Alexandria, Origen, etc.).The Areopagitics are closely related to Neoplatonism and their particularity lies in the fact that we find in them the influence of both Neoplatonic tendencies simultaneously - Origenistic (which also indirectly predetermined the dogmatic basis of Christianity) and pagan (embodied in the 5th century in the monumental philosophical and theological system of Proclus Diadochus, who made an unprecedented effort to systematise Platonism as a whole).

On a more general level, we can consider the first phase as a continuation of Plato's paideia in the direction indicated by Plato himself: refinement of philosophical discourse and hermeneutical practices in the general key of Plato's approach, without distinguishing priority directions and convincing attempts to systematise Plato's doctrine itself.

In the second phase, systematisation begins, leading to the identification of the nodal points of his teaching, including the identification of contradictions, problematic segments and conflicting interpretations. Here it is extremely important for us that Plato's teaching is for the first time subjected to correlation with theological knowledge, i.e. it is theologised. This can be seen, first of all, in the work of Philo of Alexandria, who tried to relate Plato's philosophy and cosmology of the Timaeus and the Republic to the religion of the Old Testament and its dogmatic postulates - in particular, about God the Creator, monotheism, etc. - and to the theological theology of the Old Testament. Here, for the first time, the problem arises of how Platonic ideas and Platonic demigods relate to each other and how they can be related to the personal God of Jewish monotheism. Thereafter, Philo had an enormous influence on the formation of Christian dogmatics and, consequently, the relationship between Platonism and theology in his philosophy was of fundamental importance for all that followed.

After Philo, the Christian Gnostics (primarily Basilides) became an important link in the development of Platonism. Many of them were decisively influenced by Plato, as Plotinus says in detail in Ennead II.9. But the Gnostics were already reading Plato through the prism of Middle Platonism and in particular the writings of Philo, and also in the context of early Christianity with its acute reflection on how the New Testament and the age of grace relate to the Old Testament and the age of law. With the Gnostics, this relationship took on an antagonistic expression that resulted in dualism. It is important for us that this dualism was framed through Platonic philosophy. Christian Gnosticism can therefore be said to represent a particular version of Platonism, a dualistic version.

The schools of Plotinus and Origen, i.e. Neo-Platonism proper, as the third stage in the formation of this movement, leading directly to the author of the Areopagitics, were the result of the development of Middle Platonism and to a large extent a response to the dualistic Platonism of the Gnostics. Not only Clement of Alexandria and Origen, but also Plotinus polemised with the Gnostics, and their rejection of Gnosticism prompted them to develop a dialectical and systematised Platonism that accepts the challenge of the theologising and dualism, characteristic of the Middle Platonists and the Gnostics, but gives a decidedly non-dualistic response to them. To borrow a term from Hindu philosophy, it would be fashionable to call Neo-Platonism 'advaito-platonism', i.e. non-dual Platonism.

The mystical theology of the Areopagitics falls entirely within the context of this non-dual Platonism and is a striking example of it, albeit less systematic and developed than those of Origen or Proclus. At the same time, the 5th century represents a time of waning of the dogmatic impulse that had animated the previous centuries of Greco-Roman patristics, anticipating the era of the Christian Middle Ages that followed. The style and conceptual apparatus of the Areopagitica were in the best way appropriate to this transitional period: it completed the era of Neo-Platonism, on the one hand, and Greco-Roman patristics, on the other, but it also shaped one of the most important vectors of the future development of Christian thought - including that of trans-European scholasticism, on whose formation John Scotus Eugenius to Thomas Aquinas had had such an important influence.

Translation by Lorenzo Maria Pacini

-

Is there a political philosophy in the Neo-Platonic tradition? - Daria Dugina

"Because the state is man in large format and man is the state in small format"

— Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche, in his lectures on Greek philosophy, called Plato a radical revolutionary. Plato, in Nietzsche's interpretation, is the one who surpasses the classical Greek notion of the ideal citizen: Plato's philosopher becomes above religiosity, directly contemplating the idea of the Good, unlike the other two properties (war and artisans).

This rather closely echoes the neo-Platonist Proclus' model of Platonic theology, where the gods occupy the lowest position in the hierarchy of the world. Recall that in Festugier's systematisation, Proclus' world hierarchy is as follows:

- The supra-substantial (in which there are two beginnings: the limit and the infinite),

- the mental (being, life, mind),

- intermediate (mind-thought: beyond, celestial, below),

- thought (Chronos, Rhea, Zeus),

- Deity (divine, detached, intra-cosmic heads).Plotinus places forms above the gods. The gods are only contemplators of absolutely ideal forms.

"Brought to His shore by the wave of the mind, rising to the spiritual world on the crest of the wave, one immediately begins to see, without understanding how; but sight, approaching the light, does not allow one to discern in the light an object that is not light. No, then only the light itself is visible. The object that is accessible to sight and the light that enables it to be seen do not exist separately, just as the mind and the thought-object do not exist separately. But there is pure light itself, from which these opposites then arise'.

The God-Demiurge in the Timaeus creates the world according to the patterns of the world of ideas, occupies an intermediate position between the sensible world and the intelligible world - so does the philosopher, establishing justice in the state. This is a rather revolutionary concept for ancient Greek society. It places another essence above the gods, a supra-religious and philosophical thought.

Plato's dialogue Republic constructs a non-classical psychological and political philosophy. Types of soul are compared with types of state structure, from which different conceptions of happiness are derived. The goal of each person, ruler and subordinate, is to build a fair state consistent with the ontological hierarchy of the world. It is this concept of the interpretation of politics and the soul as a manifestation of the ontological axis that Proclus Diadochos develops in his commentary on Plato's dialogues.

While it is easy to talk about Plato's political philosophy, it is much more difficult to talk about the political philosophy of the Neo-Platonic tradition. Neo-Platonism was usually perceived as a metaphysics that aimed at the deification of man ('assimilating him to a deity'), seen separately from the political sphere. However, this view of Neo-Platonic philosophy is incomplete. Proclus' process of 'assimilation to divinity', which derives from Plato's metaphysical function of the philosopher, also implies the Political is included. Deification also occurs through the political sphere. In Book VII of the dialogue Republic, in the myth of the cave, Plato describes a philosopher who escapes from the world of spears and ascends into the world of ideas, only to return again to the cave. Thus, the process of 'resembling a divinity' has a two-way direction: the philosopher turns his gaze to ideas, overcomes the world of illusion and rises to the level of the contemplation of ideas and, thus, the idea of the Good. However, this process does not end with the contemplation of the idea of the Good as the final stage - the philosopher returns to the cave.

What is this descent of the philosopher, who has reached the level of the contemplation of ideas, into the untrue world of shadows, of copies, of becoming? Is it not a sacrifice of the philosopher-director for the people, for his people? Does this descent have an ontological apologia?

Georgia Murutsu, a scholar of Plato's State, suggests that the descent has a double meaning (an appeal to Schleiermacher's reading of Platonism):

1) the exoteric interpretation explains the descent into the cave by the fact that it is the law that obliges the philosopher, who has touched the Good through the power of contemplation, to render justice in the state, to enlighten the citizens (the philosopher sacrifices himself for the people);

2) The exoteric sense of the philosopher's descent into the nether world (into the area of becoming) corresponds to that of the demiurge, reflecting the emanation of the world's mind.The latter interpretation is widespread in the Neo-Platonic tradition. The role of the philosopher is to translate what he contemplates eidetically into social life, state structures, the rules of social life, the norms of education (paideia). In the Timaeus, the creation of the world is explained by the fact that the Good (transubstantiating 'its goodness') shares its content with the world. Similarly, the philosopher who contemplates the idea of the Good, as this Good itself, pours goodness upon the world, and in this act of emanation creates order and justice in the soul and in the state.

"The ascent and contemplation of higher things is the ascent of the soul into the realm of the intelligible. If you admit this, you will understand my dear thought - if you soon aspire to know it - and God knows it is true. Here is what I see: in what is perceivable the idea of good is the limit and is barely perceptible, but as soon as it is perceptible there, it follows that it is the cause of all that is just and beautiful. In the realm of the visible it gives rise to light and its ruler, but in the realm of the conceivable it is itself the ruler on which truth and reason depend, and it is to it that those who wish to act consciously in both private and public life must look".

It is worth noting that the return, the descent into the cave, is not a unique process, but a constantly repeating process (realm). It is the infinite emanation of the Good in the other, of the one in the many. And this manifestation of the Good is defined through the creation of laws, the education of citizens. Therefore, in the myth of the cave, it is very important to emphasise the moment when the ruler descends to the bottom of the cave - the 'cathode'. The vision of the shadows after the contemplation of the idea of the Good will be different from their perception by the prisoners, who have remained all their lives in the lower horizon of the cave (at the level of ignorance).

The idea that it is the deification and the particular kenotic mission of the philosopher in Plato's State, in its Neo-Platonic interpretation, that constitutes the paradigm of the political philosophy of Proclus and other later Neo-Platonists, was first expressed by Dominic O'Meara. He acknowledges the existence of a 'conventional viewpoint' in the critical literature on Platonism that 'Neo-Platonists have no political philosophy', but expresses the conviction that this position is wrong. Instead of contrasting the ideal of theosis, theurgy and political philosophy, as scholars often do, he suggests that 'theosis' must be interpreted politically.

The key to Proclus' implicit philosophy of politics is thus the 'descent of the philosopher', κάθοδος, his descent, which repeats, on the one hand, the demiurgic gesture and, on the other, is the process of emanation of the Element, πρόοδος. The philosopher descending from the heights of contemplation is the source of legal, religious, historical and political reforms. And what gives him legitimacy in the field of the Political is precisely the 'resemblance to divinity', the contemplation, the 'rising' and 'returning' (ὲπιστροφή) that he performs in the previous phase. The philosopher, whose soul has become divine, receives the source of the political ideal from his own source and is obliged to carry this knowledge and its light to the rest of humanity.

The philosopher-king in the Neo-Platonists is not gender-specific. A female philosopher can also be in that position. O'Meara considers the late Hellenistic figures of Hypatia, Asclepigenia, Sosipatra, Marcellus or Edesia as prototypes of such philosopher rulers praised by the Neo-Platonists. Sosipatra, the bearer of theurgical charisma, as head of the School of Pergamum, appears as such a queen. Her teaching is a prototype of her disciples' ascent up the ladder of virtues towards the One. Hypatia of Alexandria, queen of astronomy, presents a similar image in her Alexandrian school. Hypatia is also known for giving the city's politicians advice on how best to govern. This condescension in the cave of people from the height of contemplation is what cost her her tragic death. But Plato himself - following the example of Socrates' execution - clearly foresaw the possibility of such an outcome for a philosopher who had descended into the Political. Interestingly, the Christian Platonists saw in this a prototype of the tragic execution of Christ himself.

Plato prepared a similar descent for himself, proposing to create an ideal state for the ruler of Syracuse, Dionysius, and being treacherously sold into slavery by the adulterous tyrant. The Neo-Platonic image of the philosopher-queen, based on the equality of women assumed in Plato's Republic, is a particularity in the general idea of the connection between theurgy and the realm of the Political. It is important for us that Plato's image of the philosopher's ascent/descent from the cave and his return to the cave has a closely parallel interpretation in the realm of the Political and the Theurgical. This is at the heart of Plato's political philosophy and could not be missed and developed by the Neo-Platonists. Another issue is that Proclus, being in the conditions of Christian society, was not able to fully and openly develop this theme, or else his purely political treatises have not come down to us. The example of Hypatia shows that Proclus' caution was not superfluous. However, being aware that ascension/descension was initially interpreted both metaphysically, epistemologically, and politically, we can consider everything Proclus said about theurgy from a political perspective. The deification of the soul of the contemplative and the theurgist makes him a true politician. Society may or may not accept him. Here the fate of Socrates, Plato's problems with the tyrant Dionysius, and the tragic death of Christ, on whose cross was written 'INRI - Jesus the Nazarene King of the Jews. He is the King who came down to men from heaven and ascended to heaven. In the context of Proclus' pagan neo-Platonism, this idea of truly legitimate political power should have been present and built on exactly the same principle: only he who has 'descended' has the right to rule. But to descend, one must first ascend. Therefore, theurgy and 'resembling a deity', while not being political procedures in themselves, implicitly contain the Politic and, moreover, the Politic only becomes platonically legitimate through them.

The 'resemblance to a divinity' and the theurgy of the Neo-Platonists contain in themselves a political dimension, which is embodied at its most in the moment of the philosopher's 'descent' into the cave.

Translation by Lorenzo Maria Pacini

-

The “Right-Wing Gramscianism” Phenomenon: The Experience of the “New Right” - Daria Dugina

The “New Right” is an ensemble of intellectual movements that appeared in 1968 as a reaction to ideological crisis and the strengthening of liberal hegemony in Europe. By 1968, the classical “rightwing” movements were riddled with liberal ideological motives, such as the adoption of capitalism, pro-American sentiments, and statism. In turn, the “left-wing” agenda, the core of which was constituted by opposition to capitalism [1], was also affected by liberal influences. Egalitarianism, individualism, the negation of differences between cultures, and universalism were rendering “left-wing” movements allies and partners of the liberal doctrine.

The “New Right” ensemble of intellectuals engaged in studying European identity, a research which differed from contemporary analogues first and foremost because it did not consider itself to be a “left-wing” or “right-wing” movement. The movement’s main ideologists spoke about the necessity of overcoming the artificial political schism and transitioning to a new doctrine, one which would be a mix of the best ideas from the “left-wing” and “right-wing” intellectual movements. As Guillaume Faye remarked at a conference of the Research and Study Group for European Civilization (G.R.E.C.E.): “Our society is no longer inspired by the renewal of its ideology. This ideology today is at its “culmination” – and therefore at the beginning of sunset, dead ideas have become moral canons, systems of habits, ideological taboos, which do not enthuse anymore” [2].

The very title “New Right” dates back to 1979, when it was impossible not to notice the influence of the “Research and Study Group for European Civilization” (G.R.E.C.E.) on the political culture and intellectual life of France. Such a “label” appeared in the summer of 1979 first in French and later European and even American media – more than 500 publications were published in just one summer, whose main goal was quite obvious: to diminish the influence of de Benoist and his supporters’ ideas. Such a media campaign only strengthened the positions of the movement – it thereby began to appear in other European countries. The New Right has accomplished the colossal work of compiling a unified set (encyclopedia) of the best European thinkers (from Plato to Nietzsche, Lorenz to Jünger). They opened up France to the ideas of the Conservative Revolutionists, the NationalBolsheviks, the philosophers of the “New Beginning”, and other phenomenologists, sociologists, social anthropologists, and ethnologists who greatly contributed to the development of European culture. Among their inspirations were Ersnt Niekisch, Ernst Jünger, Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, Oswald Spengler, Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Arnold Gehlen, Jean Thiriart, Louis Dumont, and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

A complex rethinking of European civilization and creating a front of “counter-hegemony” that would confront the universalism, globalism, egalitarianism carried out under the liberal agenda through an alternative and somewhat symmetric ideology, and also via reconstruction of European culture in all of its diversity, came to be the main tasks of the New Right. The movement initially took shape around the “Research and Study Group for European Civilization” (G.R.E.C.E.) and “New School” (“Nouvelle École”).

In 1973, the New Right launched the iconic magazine “Elements” (“Éléments”), which became a new platform for the meeting of intellectuals who set before themselves the task of reviving European Culture along the principles of holism, anti-liberalism, tradition, and anticapitalism. In 1988, the New Right launched the print publication “Crisis” (“Krisis”), a magazine for “ideas and debates”. Unlike many other political publications coming out of France at the time, the New Right’s print editions proclaimed themselves to be platforms where the opposition between “left and right” was overcome. As de Benoist wrote in the book “Les Idées à l’endroit”, the New Right practically “flipped the table of ideas” existing the time, leaving the field of the classic confrontation of “left” and “right”.

One important aspect of the New Right’s activity came to be the development of a theory of “right-wing Gramscianism.” Building on the works of Antonio Gramsci, Alain de Benoist criticizes the ideological and cultural hegemony of liberalism and declares the necessity of creating an alternative that would be founded on the values of European civilization – holism, tradition, a pluriversal perception of the world, Europe’s continental identity, and replacing abstract “human rights” with “peoples’ rights”. De Benoist has remarked: “In a sense, and if we stick to only methodological aspects of the culture’s power (pouvoir culturel) theory, some views of Gramsci are virtually prophetic” [3].

One of G.R.E.C.E.’s conferences (the XVI colloque national), which took place on 29 November 1981 in the Palais des Congrès in Versailles, was devoted to the topic of “right-wing Gramscianism”. At the opening of the G.R.E.C.E. conference on “right-wing Gramscianism”, Professor M. Vayof of Nancy-Université emphasized: “To be Gramscianists for us is to admit the importance of cultural power (pouvoir culturel) theory: we are not talking about preparing the rule of some political party, rather, we want to transform the mentality to support a new system of values, where the political translation [political area] does not interest us at all” [4]. Alain de Benoist, the historian of ideas and chief ideologist of G.R.E.C.E., also remarked that political processes change all the while as the “ideological majority” remains the same”: “Now we can talk about a consent, rather than a contradiction between the political, ideological and sociological majority. Such consent represents the main state of affairs” [5]. From de Benoist’s point of view, “left-wing” ideology, riddled with liberal tendencies (individualism, priority of the economic sector over all others), has created a climate in which no political development can take place. For de Benoist, it is important to highlight the fact that behind the façade of “left-wing” ideas in recent decades hides the very same liberalism (liberal ideology and culture) and “consumer society”. The goal of right-wing Gramscianism is to get out of the system of liberal hegemony through the development of alternative culture and metapolitical codes. De Benoist describes such a way out of the “universalist” culture in existential categories: “We are at midnight, we are at the prime meridian of active nihilism. <…> Participation in our enterprise does not mean choosing one clan against another. It means getting out of the trolleybus, which does nothing but drives across the opposite poles of the same ideology – with or without stops” [6]. De Benoist notes that we are talking about “changing the universe”, “giving the world its color, memory – its measures, peoples – their historical opportunity and fate of being” [7]. For the New Right, ideas become weapons. As Guillaume Faye remarked:

“Isolated intellectuals, neutral, not at war, have never marked history with their stamp. <…> G.R.E.C.E. and our entire movement does not at all intend to give ideology to liberals or conservatives, as well as to the “leftwingers”, but wants to bring into society, in all its complexity, the strength of different ideas. To execute “right-wing Gramscianism” means to spread a system of values that:

— will work for a long time;

— will contain competing formulas;

— will be brought in through a metapolitical strategy;

— will be located outside political institutions.

G.R.E.C.E. also spreads a view of the world (which can be expressed through action in the cultural sphere, or in a purely intellectual sphere) through the construction of a theoretical corpus, which is never complete, but always developing. Such a corpus presupposes the inclusion of many disciplines in it – from biology to philosophy” [8].

Also in his speech at the G.R.E.C.E. conference on right-wing Gramscianism, he emphasized that “the ideological corpus [G.R.E.C.E.] is radically open, is in constant evolution, unites new disciplines, accepts new ideas, is in constant interaction with reality”.

“Right-wing Gramscianism” thus reveals the dominance of liberalism in the field of culture and advocates the construction of counter-hegemony. For the New Right, the positions of “right-wingers” in relation to liberal hegemony in culture are not suitable, as the “rightwing” refrains from engaging in the war for ideas. De Benoist considers the latter to be a fatal mistake (Caesarism), insofar as losing and leaving culture to liberalism leads to any politics inevitably turning into a liberal politics. But de Benoist also views the “left-wing” opposition to liberal culture as ineffective. Capitalism in both the “rightwing” and “left-wing” intellectual space becomes a kind of code which can only be resisted by an alternative code.

In positioning and describing such a “right-wing Gramscianism”, “independence from ideologies” is also important. Representatives of the “New Right” have formulated the idea that the ideologies of the Modernity which have been in strict opposition and state of struggle are a phenomenon exclusive to Western culture. The position of the right-wing Gramscianism is based on the idea of building a “territory free of ideologies.” This territory would reject “individualism”, egalitarianism and the concept of abstract human rights (which are interpreted by the “New Right” to be a forgery of liberal doctrine).

Right-wing Gramscianism is thus conceived as a territory of metapolitics beyond the influence of hegemony, that is, the authority of liberal culture with its algorithms, practices and institutions. Gramsci himself viewed communism as an alternative to hegemony or counter-hegemony, primarily in its active Leninist version, where politics is ahead of economics and culture is ahead of politics. G.R.E.C.E. however, attributes contemporary communism to hegemony, i.e., they interpret it to be an extremely “left-wing” version of liberalism itself.

And then the thesis of right-wing Gramscianism acquires all its meaning: it is an invitation to create a new version of counter-hegemony that would challenge the entire political theology of modern times. From Gramsci, however, the “New Right” took, first of all, the thesis that the source of power should be sought precisely in culture, in the historical pact that the intellectual freely concludes with this or that historical dominant.

De Benoist chooses the side of Labor against Capital (in this he is a consistent Gramscianist), but he interprets the principle of Labor (Arbeit) rather in the spirit of Ernst Jünger and his Worker (der Arbeiter). Again, here we are not talking about nationalism as another version of the same capitalist culture (and, therefore, about another version of the same hegemony), but about going beyond the borders of Modernity as a whole, into yet unknown territory – beyond “right” and “left”.

Therefore, “right-wing Gramscianism” is only a conventional name. It is not so much “right-wing” as “non-left-wing”, i.e., it does not recognize communism to be an adequate counter-hegemony. But it is also not “right-wing” in the conventional sense, since it rejects capitalism and nationalism. Later, the French sociologist Alain Soral, who continued this line, would call this counter-hegemonic synthesis “Left-wing Labor + Right-wing Values.”

This is most fully reflected in the Fourth Political Theory, to which A. de Benoist came already in the 2000s. Here, as in Gramsci, an antithesis to hegemony (including its interpretation by Gramsci himself as international – imperialist – capitalism) is posed and the primacy of culture is recognized. But Marxism – at least in its dogmatic version – is discarded and a free search begins for philosophical, sociological and anthropological studies that do not fall under the classical criteria and which can come to form the basis of a new metapolitical topology.

In 40 years, the New Right has come a long way in developing their metapolitical theory and related strategies. To date, the conceptual apparatus and theoretical algorithms developed by them are the most adequate for the interpretation of such phenomena as European populism, the crisis of globalism, and the emergence of multipolarity. This is increasingly recognized not only by the “right”, but also by the “left”, such as the Italian communist Massimo Cacciari, the French sociologists Serge Latouche and K.-M. Mishea, and the left-wing intellectual Chantal Mouffe.

References:

[1] Pour un gramscisme de droite. Acte du XVIe colloque national du GRECE. Paris: Le Labyrinthe, 1982. P. 72.

[2] A. de Benoist, Les Idées à l’endroit. Paris: Editions Libres Hallier, 1979. P. 258. [

3] Pour un gramscisme de droite. Acte du XVIe colloque national du GRECE. Paris: Le Labyrinthe, 1982. P. 7.

[4] Ibid. P. 11.

[5] Ibid. P. 21.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

Translated by Jafe Arnold

From The Theory of Hegemony and Counter-hegemony

Almanac by “Sun of the North”

-

The Universe of Platonic Thought - Daria Dugina

We publish the talk by Daria Dugina, former researcher of Political Philosophy at Moscow State University, given during the 16th International Conference “The Universe of Platonic Thought” in St. Petersburg on August 28-30, 2018.

Political philosophy has always been denied full recognition, focusing on analyzing the metaphysical aspects of Neoplatonism. Neoplatonic concepts such as “permanence” (μονή), “emanation” (πρόοδος), “return” (ὲπιστροφή), etc. were treated in historical-philosophical works separately from the sphere of the Political [1]. Thus, the Political was interpreted only as a stage of ascent toward the Good, embedded in the rigid hierarchical model of Neoplatonic philosophical thought, but not as an independent pole of the philosophical model.

This view of the Neoplatonic philosophical heritage seems insufficient to us. We would like to take the example of Proclus' works to show that in Neoplatonism the Political is interpreted as an important and independent phenomenon embedded in a general philosophical, metaphysical, ontological, epistemological, and cosmological context.

While in classical Platonism and in Plato himself political philosophy is explicitly expressed (dialogues “State”, “Politics”, “Laws”, etc.), in Neoplatonism and especially in Proclus we can judge the philosophy only indirectly and mainly in commentaries on Plato's dialogues. This is also due to the political-religious context of the society in which the later Neoplatonists, including Proclus himself, operated.

At present, the political ideas of the Neo-Platonists have not been sufficiently studied, and, moreover, the very fact of the existence of Neo-Platonic political philosophy (at least in the late Greek Neo-Platonists) has not been proven and is not the subject of scientific and historical-philosophical research. However, Neoplatonic systems of political philosophy were widely developed in the Islamic context (from al-Farabi to Shiite political gnosis [2]), and Christian Neoplatonism in the versions of Western authors (in particular, Blessed Augustine [3]) largely influenced the political culture of medieval Europe.

At present, the topic is underdeveloped. In Russian there are practically no research works devoted specifically to Proclus' political philosophy. Among foreign sources, the only specialized studies are “Platonopolis” by Dominic O'Meara, the English specialist in Neoplatonic philosophy [4], “Founding Platonopolis: Platonic Polytheism in Eusebius, Porphyry and Jamvlich [5], separate chapters in “Proclus. Neoplatonic Philosophy and Science” [6] and comments by A.-J. Festujer to French translations of Proclus' major works, especially the five-volume “Commentaries on Timaeus” [7] and the three-volume “Commentaries on the State” [8].

Proclus Diado (412-485 CE) was one of the most important thinkers of late antiquity, a philosopher whose works express all the main Platonic ideas developed over many centuries. His writings combine religious Platonism with metaphysical Platonism; to some extent he is a synthesis of all previous Platonism-both classical (Plato, Academia), “middle” (described in J. Dillon [9]), and Neoplatonism (Plotinus, Porphyry, Jambleach). Proclus was probably the third scholar of the Athenian school of Neoplatonism (after Plutarch of Athens and Syrianus, Proclus' teacher), which existed until 529 (until its closure by Justinian, who issued edicts against pagans, Jews, Arians and numerous sects, and denounced the teaching of the Christian Platonist Origen).

Proclus' philosophical hermeneutics is an absolutely unique event in the history of the philosophy of late antiquity. Proclus' works represent the culmination of the exegetical tradition of Neoplatonism. His commentaries start from Plato's original works but take into account the development of his ideas, including the criticisms of Aristotle and the Stoic philosophers, in the most detailed way. Added to this was the tradition of Middle Platonism, in which special emphasis was placed on religious theistic issues [10] (Numenius, Philo of Alexandria). Plotinus introduced the thematization of the Apophatic into exegesis. Porphyry drew attention to the doctrine of political virtues and virtues that appeal to the mind. James [11] introduced a differentiation in the Plotinian hierarchy of the basic ontological and eidetic series represented by gods, angels, demons, heroes, etc. If in Plotinus we see the main triad of the Elements - the Unity, Mind and Soul, in James the multi-stage eidetic series separating people from the World Soul and the speculative realms of Mind. James also belongs to the practice of commenting on Plato's dialogues in esoteric terms.

For an accurate reconstruction of Proclus' political philosophy, it is necessary to pay attention to the political and religious context in which he operated.

Politically, Proclus' era is very eventful: the philosopher witnesses the destruction of the western frontiers of the Roman Empire, great migrations of peoples, the invasion of the Huns, the fall of Rome, first at the hands of the Visigoths (410), then at the hands of the Vandals (455), and the end of the Western Empire (476). One of Proclus' chosen visitors to the school, Anthemius, a patrician of Byzantium, took an active part in political activities.

Proclus (according to the traditional rules of interpretation of Plato's dialogues) begins his commentary on the State and Timaeus with an introduction in which he defines the topic (σκοπός) or intention (πρόθεσις) of the dialogue; describes its composition (οἷκονομία), genre or style (είδος, χαρακτήρος), and the circumstances under which the dialogue took place: the topography, the time, the participants in the dialogue.

In determining the topic of the dialogue, Proclus points out the existence in the philosophical tradition of analysis of Plato's “State” of different points of view [12]:

- some are inclined to see the subject of the dialogue as a study of the concept of justice, and if a consideration of the political regime or the soul is added to the conversation about justice, this is only one example to better clarify the essence of the concept of justice;

- others see the analysis of political regimes as the object of the dialogue, while the consideration of justice issues, in their view, in the first book is only an introduction to the further study of the Political.

We thus encounter some difficulty in defining the object of the dialogue: does the dialogue aim to describe the manifestation of justice in the political sphere or in the mental sphere?

Proclus believes that these two definitions of the subject of dialogue are incomplete and argues that both goals of dialogue writing share a common paradigm. “For what justice is in the psyche, justice is the same in a well-governed state” he says [13]. In defining the main topic of the dialogue Proclus notes that “the intention [of the dialogue] is to [consider] the political regime, then [consider] justice. It cannot be said that the main purpose of the dialogue is exclusively to try to define justice or exclusively to describe the best political regime [14]. Having admitted that the political and justice are interconnected, we will note that in the dialogue there is also a detailed consideration of the manifestation of justice in the sphere of the mental. Justice and the state are not independent phenomena. Justice is manifested at both the political and the psychic (or cosmic) level.

Once this fact is established, the next question arises: which is more primary-the soul (ψυχή) or the state (πολιτεία)? Is there a hierarchical relationship between the two entities?

The answer to this question is found in the dialogue “The State” [15] when Plato introduces the hypothesis of homology (ὁμολογία) of soul and state, the sphere of the mental and the political. This forces us to think carefully about what is meant by homology in Plato and the Neoplatonists who continued his tradition. In the later New Age philosophy, the (real) paradigm is mostly a thing or object, and ontology and epistemology are hierarchically constructed: for objectivists (empiricists, realists, positivists, materialists) knowledge will be understood as a reflection of external reality, for subjectivists (idealists) reality will be interpreted as a projection of consciousness. This dualism will be the basis for all kinds of relations in the field of ontology and epistemology. But to apply such a method (objectivist or subjectivist) to Neoplatonism would be anachronistic: here neither the state nor the soul nor their concepts are primary. In Plato and the Neoplatonists the primary ontology is endowed with ideas, paradigms, while the mind and soul and the sphere of the political and cosmic represent reflections or copies, icons, results of eikasia (εικασία). Consequently, in the face of the exemplar, any kind of copy: whether political, mental, or cosmic, possesses an equal nature, an equal degree of distance from the exemplar. They are not seen through comparison with the other, but through comparison with their eidetic prototype.

The answer to the question about the primacy of the Political over the psychic or vice versa then becomes clear: it is not the Political that copies the psychic or vice versa, but they are homologous to each other in their secondness to a common image/eidos.

The recognition of such homology is the basis of Proclus' hermeneutic method. For him, state, world, mind, nature, theology and theurgy represent eidetic chains of manifestations of ideas. Therefore, what is true of justice in the realm of the Political (e.g., hierarchical organization, the placement of philosopher-guardians at the head of the state, etc.) concerns at the same time the organization of theology-the hierarchy of gods, daimons, souls, etc. The existence of a model (paradigm, idea) ensures that all orders of copies have a unified structure. It is this that makes it possible to safely deduce Proclus' political philosophy from his vast legacy, in which actual politics is given little space. Proclus implies the Political in the same way as Plato, but unlike the latter he makes the Political the main theme much less frequently. Nevertheless, any interpretation of Plato's concepts by Proclus almost always implicitly contains analogies in the area of the Political.

General homology, however, does not negate the fact that there is some hierarchy among the copies themselves. The question of the hierarchy of copies among themselves has been approached differently by different commentators on Plato. For some, closer to the paradigm, the model is the phenomenon of the soul, for others the phenomenon of the state level, and for still others the cosmic level. The construction of this hierarchy is the space for freedom in interpreting and hierarchizing the virtues. Thus, for example, in Marin[16] Proclus' own life is presented as an ascent up a hierarchical ladder of virtues: from the natural, moral, and social to the divine (theurgical) and even higher, unnamed, through the purifying and speculative. The political virtues are usually considered intermediate.

From the fragment we quoted above, in which Proclus discusses the topic of the dialogue on the state, we can see his desire to emphasize that the hierarchy of interpretations is always secondary to the basic ontological and epistemological structure of Platonism as a contemplative method. Thus, the construction of a system of hierarchies in the course of interpretations and commentaries turns out to be secondary to the construction of a general metaphysical topology reflecting the relationship between exemplar and copies. And even if Proclus himself, in the course of the development of his commentary, pays situatively more attention to mental, contemplative, theurgical, and theological interpretations, this, by no means, means that political interpretation is excluded or of secondary importance. Perhaps in other politico-religious circumstances, which we discussed in the first part of our paper, describing the political situation of Proclus' time in the context of Christian society, Proclus could have focused more on political hermeneutics without violating the general structure and fidelity to Platonic methodology. But, in this situation, he was forced to talk about politics in less detail.

Proclus' interpretation of the “State” dialogue, where Plato's theme is the optimal organization of the state (polis), represents a semantic polyphony, a polyphony that implicitly contains whole chains of new homologies. Each element of the dialogue interpreted by Proclus, from the perspective of psychology or cosmology, corresponds to a political equivalent, sometimes explicitly, sometimes only implicitly. Thus, the commentaries on Plato's dialogue, thematizing precisely “polytheia”, do not represent for Proclus a change from the usual register of consideration of ontological and theological dimensions in most of his other commentaries. By virtue of his homology, Proclus can always act according to circumstances and freely complete his hermeneutical scheme, deploying it in any direction.

Notes:

[1] Karl Schmitt's term to emphasize that it is not a technical organization of the process of government and power, but a metaphysical phenomenon with its own internal metaphysical structure, an autonomous ontology and “theology”, from which C. Schmitt's formula “political theology” originated. See Schmitt C. “Der Begriff des Politischen”. Text of 1932 with a paper and three corollaries. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1963; Schmitt C. Political theology. Canon Press-C, 2000.

[2] Corbin Henri. “History of Islamic philosophy” Progress-Tradition, 2010.

[3] Mayorov G.G. “The formation of medieval philosophy (Latin patristics)”. Mysl, 1979; “Augustine. On the city of God”, Harvest, M.: Astra, 2000.

[4] O'Meara D. J. “Platonopolis. Platonic political philosophy in late antiquity”, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003.

[5] Schott J. M. “Founding Platonopolis: The Platonic Politeía in Eusebius, Porphyry, and Iamblichus” Journal of Early Christian Studies, 2003.

[6] Siorvanes Lucas. “Proclus. Neoplatonic philosophy and science”, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 1996.

[7] Proclus. Commentaries on Time. Tome 1, Livre I ; tr. André-Jean Festugière. Paris : J. Vrin-CNRS, 1966; Idem. Commentaries on time. Tome 2, Livre II ; tr. André-Jean Festugière. Paris : J. Vrin-CNRS, 1967; Idem. Commentaries on time. Tome 3, Livre III ; tr. André-Jean Festugière. Paris : J. Vrin-CNRS, 1967; Idem. Commentaries on time. Tome 4, Livre IV ; tr. André-Jean Festugière. Paris : J. Vrin-CNRS, 1968; Idem. Commentaries on time. Tome 5, Livre V ; tr. André-Jean Festugière. Paris : J. Vrin-CNRS, 1969.

[8] Proclus. Commentaries on the Republic. Tome 1, Livres 1-3 ; tr. André-Jean Festugière. Paris : J. Vrin-CNRS, 1970. Idem. Commentaries on the Republic. Volume 2, Livres 4-9 ; tr. André-Jean Festugière. Paris : J. Vrin-CNRS, 1970; Idem. Commentaries on the Republic. Tome 3, Livre 10 ; tr. André-Jean Festugière. Paris : J. Vrin-CNRS, 1970.

[9] Dillon J. The Middle Platonists of 80 B.C. - 220 A.D.. St. Petersburg. Aletheia, 2002.

[10] In the ethical teaching of the Middle Platonists the central idea proclaimed is the goal of being assimilated into the divine.

[11] Jamvlich also systematizes the method of commentary on Plato's dialogues, introducing the division into different types of interpretation: ethical, logical, cosmological, physical, and theological. It is his method of commentary that will form the basis of Proclus'. He distinguished the twelve Platonic dialogues into two cycles (the so-called “Cane of James”): the first cycle included dialogues on ethical, logical and physical problems, the second - the more complex Platonic dialogues, which were studied in the Neoplatonic schools in the last stages of education (“Timaeus”, “Parmenides” - dialogues related to theological and cosmological problems). Iamvlich's influence on the Athenian school of Neoplatonism is extremely great.

[12] Proclus. Commentary on the Republic. Trad. par A.J. Festugière. Op. cit. pagg. 23-27.

[13] Proclus. Commentary on the Republic. Trad. par A.J. Festugière. Op. cit. pag. 27.

[14] Proclus. Commentary on the Republic. Trad. par A.J. Festugière. Op. cit. pag. 26.

[15] Plato “The State” Works in four volumes. Volume 3. Part 1. St. Petersburg: St. Petersburg University Press; Oleg Abyshko Publishing, 2007.

[16] Marin “Proclus, or on happiness”, “Diogenes of Laertes. On the life, doctrines and sayings of the famous philosophers” Thought, 1986. С. 441-454.Translation by Lorenzo Maria Pacini

-

Metaphysics of War - Daria Dugina

Lecture by Daria Dugina at the Russian Student Club on 1 April 2021. Daria analyses the phenomenon of war from the perspective of Platonism, Neoplatonism and the subsequent philosophical tradition.

Today I would like to share my views on the metaphysics of war and the philosophical comprehension of what is happening. Without such comprehension, we will not be able to grasp the full depth of the current confrontation. It goes without saying that I am carefully watching the information space, commenting on it live. However, today I would like to have a look at the current events from a philosophical perspective.

Basically, war has always been perceived as something necessary. Heraclitus calls it the "father of things." War has always constituted peace. If there is no war, there is no division, but there is no peace. Thus, in a sense, war is comprehended as a cosmological act. War theorists Thucydides and Socrates romanticized war. At the same time, a very interesting division is taking place. It seems to me that it is crucial for us today when analyzing the conflict. The wars are divided into good and bad.

Good wars are wars against an external enemy. They are acceptable according to Thucydides, or Socrates, or Xenophon. Besides, there are internecine wars that are viewed negatively. Later, in Plato's dialogue Laws, these will be characterized as external wars. Plato uses the Greek term "polemoy" (pólemoj), as opposed to internal war - discord. Naturally, the ancient Greeks justified wars with an external enemy. An external war was seen as a war with others, with strangers, with barbarians, who, generally, can be subdued. Whereas a discord war, which the Greek policies used to wage too, such as the war of Athens and Sparta, according to Plato and his predecessors, should have led to reconciliation, but by no means to destruction.

Talking about today's conflict, the confrontation between Russia and Ukraine, the question arises. Is it an external or an internecine war? That's a very tricky question. Just yesterday, I spoke on the Republic TV channel. My opponent, a Ukranian colleague Polina from Kyiv, an ex-adviser to the Minister of Defense, said, I quote: "There is no such people as Russians, but if they exist, they have to be killed." After hearing it I concluded that this war (although it can rather be called not a war, but a peace enforcement) is no longer internecine, it is being waged with an external enemy. That is, those who oppose us, who commit acts of aggression, who have been committing acts of aggression against the Russian people for eight years and who forbade the Russians to live, forbade them to speak their language, forbade them to have their culture, they are no longer our brothers Slavs. This is some other entity.

I was occupied by this thought, i.e., an attempt to comprehend the conflict as a struggle with an external enemy, as a "polemoy". And this "polemoy" according to Plato must be waged very courageously. Also, war, according to Plato, is, in many respects, a consequence of human imperfection. Nevertheless, it must be waged fairly and it must establish the correct order. The higher is the contemplative principle, and the lower is the lustful principle.

If we look at the structure of Ukrainian power, we'll see that over the past eight years since 2014, US military subsidies have amounted to $20.5 billion in large military equipment equivalent. The same happens in other areas. Talking about the total volume of investments in civil society by foundations the way I see it, the total sum was much less there, up to $1.5 billion, I guess. But it is big money anyway.

If you look at these proportions then the question arises whether Ukraine is a puppet state ruled by a comedian, by the way, it is already ridiculous. What an interesting sacred symbol it is. For example, Heraclitus was called the "weeping philosopher" for he never laughed. Democritus, on the other hand, was called the "laughing philosopher" because he laughed all the time and he was a kind of a damned man for antiquity. It is no coincidence that his books were burned by Platonists and Pythagoreans. And by Plato himself, according to the legend.

Anti-Russia and its front is not just a political front, but rather an oppositional geopolitical pole. It is some kind of a proxy actor of the American principle, American civilization, American order, i.e., a globalist order. It also serves as another anti-Russian model, both existential and metaphysical. This is a model where values are turned upside down. Lust rules there, that is, the lustful lower principle that is associated with the idea of "stomach" in Plato. The Russian Ministry of Defense has announced today that our country did not start hostilities, but on the contrary, Russia is putting an end to them. And the end of these hostilities is actually the restoration of justice.

You may recall, since you have already mentioned philosophical concepts, a concept of just war as well. It applies here. And by the way, this just war is taken as an argument by many neoconservatives when conducting military operations in the world. Look how differently we act. They just reduce to rubble all the neighborhoods, as they did in Iraq. Mass shelling of residential and non-residential areas. Their private military companies shoot civilians. On the opposite, we are acting for the sake of the living. Despite the misconceptions and mistakes, despite the fact that the Ukrainian people were fascinated and even hypnotized by the narrative, a different logos, which is alien to them, the Russian peacekeepers do not want them dead.

Everyone is saying now that this operation should have been completed in a day. No, it shouldn't have. Because it is a very complex process. However, on the whole, we see that the Russians behave very humanely when establishing this sacred order. Not in the way the lustful principle operates. Not committing war crimes.

In principle, these are the main points that I wanted to share with you. There is something to think about and discuss. It turns out that, on the one hand, the Russians are waging war with an external enemy, the United States. On the other hand, they understand that the bodies of the people from that other side are external to us. The bodies and the souls of these people are our own reflection. But this is a reflection that has wandered into a distant and completely wrong world of a different ontology, with a different hierarchy of values. Therefore, on the one hand, this is an external war, the war with an external enemy, with external civilizations, with the logos of Cybele, with the logos of lust, even with the myth of lust, with obsession. With consumption, too. What is happening in Ukraine is a true society of performance. As my colleague just noted before me, there is an asymmetry in the information war. On the other hand, this is an internal war as well. This is a kind of discord that should lead to peace. Actually, this is a discord between the two principles of one soul, as Plato put it. There are two principles of the soul: a herdsman and a horse. Thus, our Russian military are similar to a herdsman who is trying to pacify this raging black horse.